Arkansas public school teachers were hanging bulletin boards, filing lesson plans and otherwise armoring up for the school year ahead on the afternoon of Aug. 11, the Friday before the first day back for most students. That’s when the phone calls came in.

State officials rang educators at the six Arkansas high schools where Advanced Placement African American Studies would be on offer to let them know their plans would have to change.

During the phone call, teachers learned the Arkansas Department of Education would not count AP African American Studies toward graduation requirements, nor would it cover exam fees as it does for every other AP course. And students hoping for a bump to their grade point average would be disappointed because without state approval, the AP African American Studies class could not be graded on the 5.0 scale reserved for AP courses, education department officials said.

Those last-minute calls layered confusion and upheaval atop the usual back-to-school stress, as educators scrambled to understand what this eleventh hour ambush to the class schedules of hundreds of Arkansas students would mean, exactly. The state sent no email and provided nothing in writing, and the education department’s website gave zero guidance to schools, leaving teachers only two days to figure it out before students took their seats.

If the goal of those Friday afternoon calls was to sow enough confusion to coerce Arkansas public schools to drop the class, it backfired.

Within a week, educators called the Arkansas Department of Education’s bluff. All six schools would keep AP African American Studies on offer, despite threats that the course might violate an executive order by Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders and a new state law targeting “indoctrination” and prohibited topics in public school classrooms. State education officials agreed to create a new course code for the class, freeing up districts to offer it for “local credit” and weigh it on the elevated 5.0 scale.

Outrage blazed across social media, spurring Arkansans and civil rights advocates from around the country to pledge the cash to cover students’ exam fees.

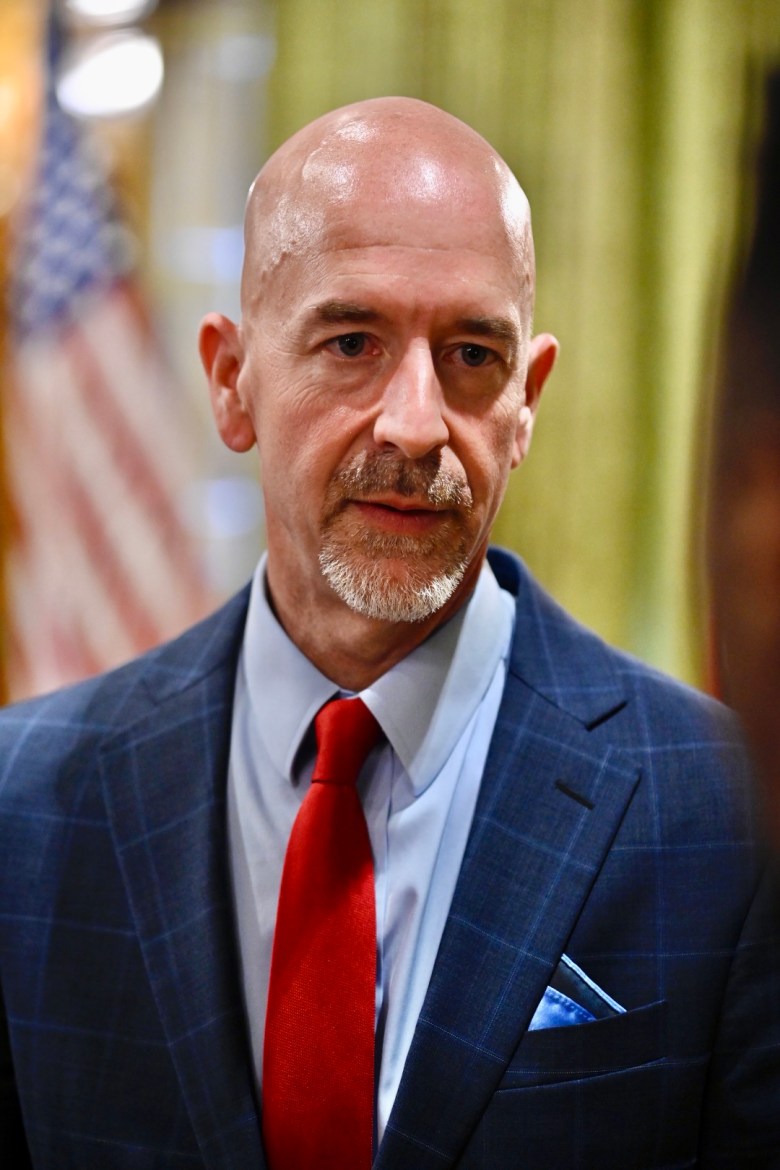

For a moment, it looked as if the state might back down. But on Aug. 21, Sanders and Arkansas Education Secretary Jacob Oliva landed their next blow.

Teachers would be required to submit lesson plans and course materials by Sept. 8 to be inspected for evidence of indoctrination and critical race theory. “Given some of the themes included in the pilot,” Oliva’s letter stated, “including ‘intersections of identity’ and ‘resistance and resilience,’ the Department is concerned the pilot may not comply with Arkansas law, which does not permit teaching that would indoctrinate students with ideologies, such as Critical Race Theory (CRT).”

Excuses pile up

The College Board, the New York-based nonprofit that administers AP exams and develops curriculum guides, has been developing an AP African American Studies class for years. The course was first piloted in 60 schools nationwide last year, including two in Arkansas: The Academies at Jonesboro High School and Little Rock Central High.

The College Board expanded its AP African American Studies pilot in the 2023-24 school year to roughly 16,000 students in 740 schools across 40 states and the District of Columbia. History teachers at North Little Rock High School, Jacksonville High School, North Little Rock Center for Excellence and eStem High School joined the new veterans from Central and Jonesboro over the summer to train and prepare to offer the class.

It remains a mystery why the Arkansas Department of Education waited until the Friday before school started to erase AP African American Studies from the state’s database of accepted courses, which had included the class since 2022. The department didn’t answer questions about the timeline. We know only that on the morning of Saturday, Aug. 12, the ADE sent a terse email to district curriculum administrators noting the change to the database but offering no explanation or guidance.

While he and his staff dodged questions from reporters through the weekend, the education secretary pitched a hazy set of excuses in a phone call with Little Rock School District Superintendent Jermall Wright.

Oliva falsely suggested the course would not be recognized by colleges and universities, when in fact more than 200 schools (including the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville) were already signed on to honor the course for credit. Oliva reportedly went on to claim that he didn’t think the state should offer AP courses that may not qualify for college credit. Never mind that there’s not a single AP course anywhere that comes with such a guarantee, since colleges make their own rules on which credits to accept — yet Arkansas schools continue to offer dozens of them.

Then, on Monday, Aug. 14, with public school classes already underway, the Arkansas Department of Education put out its official statement, denigrating the academic quality of AP African American Studies and suggesting its curriculum is based on ideology rather than facts and history.

“The department encourages the teaching of all American history and supports rigorous courses not based on opinions or indoctrination,” the statement said.

Oliva tried yet another excuse that afternoon, telling the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette that AP African American Studies lacked an “AP course audit” required by the state. The College Board confirmed to the Arkansas Times, however, that the audits are complete for all six Arkansas high schools offering the course.

A MAGA governor and her Florida man

Perhaps we should have seen it coming. Sanders issued an executive order in her early days in office requiring that all Arkansas public school curricula be scrubbed of “indoctrination” and “critical race theory,” two slippery and legally undefined terms that nevertheless possess the power to rile conservative voters. Section 16 of the LEARNS Act, Sanders’ signature legislation, takes aim at supposed indoctrination and critical race theory in public schools.

Who better to scour Arkansas public school classrooms for signs of forbidden lessons than an import from Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis’ administration? As a senior chancellor for the Florida Department of Education from 2017 to 2022, Oliva was part of a campaign to reject woke math books and attack school district policies deemed too accepting of gay and transgender students and staff.

As Oliva was leaving Florida to take the Arkansas job in January, DeSantis was announcing that Florida would ban AP African American Studies under a new state law called the Stop WOKE Act. DeSantis mocked the class, saying it had no educational value and claiming the College Board changed the curriculum in response to his concerns. The College Board disputed DeSantis’ claims, saying they had made changes based on feedback from educators and scholars, not Florida officials, though the group acknowledged they struggled to craft the course in a charged political climate where criticism flies at them from both sides.

While DeSantis reveled in his battle with the College Board, Arkansas’s governor kept quiet in the days after her education department nixed the course. Sanders’ spokeswoman fired her standard insults at journalists and her boss’ critics on social media. But as national media attention mounted, the governor seemed content to let her education secretary absorb the blowback. The nine members of the state Board of Education, the governor-appointed body to whom Oliva reports, also remained in the background.

When Sanders did eventually speak up, she took her usual route straight out of town. The governor bypassed Arkansas media and went to Fox News instead, where she could unload her practiced and poll-tested talking points about “this propaganda leftist agenda, teaching our kids to hate America and hate one another” to a right-wing national audience.

Outrage

That Sanders herself graduated from Central High but is still willing to accuse its teachers of indoctrinating students is bound to leave some fellow members of the class of 2000 confused.

But Sanders sacrificed whatever goodwill was left for her at Central High months ago during her rebuttal to President Biden’s Feb. 7 State of the Union, when she equated the Little Rock Nine’s courageous integration of the previously all-white school with her own school privatization scheme.

“I believe giving every child access to a quality education — regardless of their race or income — is the civil rights issue of our day,” Sanders said. “Tomorrow, I will unveil an education package that will be the most far-reaching, bold, conservative education reform in the country.” That package turned out to be Arkansas LEARNS, the bill that included a crackdown on “indoctrination” in the classroom and a voucher program that redirects public money to pay private school tuitions.

Within a month, hundreds of Central students and alumni had signed an open letter requesting that the governor kindly keep their school’s name out of her mouth. “As much as she tries to desperately cling to the legacy of our historic institution, we, as students of Central High, unequivocally reject her exploitation of our school’s achievements,” the letter said.

On March 3, more than a thousand Central High students walked out of class to protest the attacks on academic freedom and public school funding codified in Sanders’ LEARNS Act.

Sanders and her education secretary seem unbothered by charges of racism from students, Black legislators, the NAACP and national media — or even from members of the Little Rock Nine themselves.

“I think the attempts to erase history is working for the Republican Party. … They have some boogeymen that are really popular with their supporters,” Elizabeth Eckford told NBC News in response to news of Arkansas’s move to discredit AP African American Studies. Eckford, now 81, is the teenage girl wearing dark glasses in the now iconic photograph of a mob of white students shouting abuse at their Black classmates outside Central High.

Another member of the nine, Terrence Roberts, told NBC that state bans on critical race theory are “ridiculous” and applauded the high school for forging ahead with AP African American Studies. “The question is, will they be successful?” Roberts, 81, said.

Arkansas Democratic Black Caucus President Debrah Mitchell drew the obvious parallel between 1957 and today in an open letter to Oliva.

“It was almost 66 years ago that Governor Orval Faubus ordered the Arkansas National Guardsmen to block nine Black students from entering Central High School the night before classes began,” Mitchell wrote. “This nearly midnight action by your department is eerily reminiscent of those tactics from 1957. Rather than physical barriers, this recent change has created financial and logistical obstacles for students hoping to boost their GPAs with AP college credits, and for teachers who prepared the course materials.”

Central High student Vivian Day, who took AP African American Studies last year during its first pilot phase, said the class taught her to recognize ploys like the one the state of Arkansas is using now.

“As someone who took the class last year, I know firsthand how political attacks manage to undermine the ability of students to learn valuable information about the history and culture of African Americans,” she said.

It remains unclear just how much pressure the state intends to exert on how Black history is taught in Arkansas schools. AP African American Studies will proceed as planned in the six pilot schools in the 2023-24 school year. But will the education department’s insistence on reviewing lesson plans and course materials limit how the course will be taught? Will other high schools around the state steer clear of offering AP African American Studies in future years, fearing they could be the next target of the Sanders administration’s scrutiny?

An Aug. 22 meeting between Sanders, Oliva and a group of Democratic lawmakers yielded no real progress. Sanders and Oliva declined to provide solid definitions or examples of the indoctrination teachers have been warned to avoid. The ongoing lack of clarity means history teachers will just have to make their best guesses to stay on the right side of nebulous legalese.

And, while a relatively small number of Arkansas students will ever take AP African American Studies, might the education department’s warnings about the dangers of critical race theory influence how American history is taught more generally? Teachers inclined to emphasize the evils of slavery, Jim Crow and ongoing systemic racism in their classes may tread more carefully now. Teachers inclined to play down or largely ignore those subjects may feel vindicated.

Meanwhile, along with educating the next generation, Central continues its dual role as a landmark of the ongoing civil rights struggle that’s landed once again at its front steps.

Robin White, superintendent of the Little Rock Central High National Historic Site, said the National Park Service’s mission is to share the school’s desegregation story in full.

“Our job is to address controversy and conflict. You can’t have change without resistance,” she said. “Controversy and conflict are at the heart of the story.”

Asked about the current situation, White chose her words carefully. “We fully support education and learning the complete and complicated history of this nation,” she said. “We cannot pick and choose what we want to learn.”

How this particular chapter ends, though, is anyone’s guess. What might a future exhibit about our current-day struggle look like? “We will have to see who falls on the right side of history,” White said.